The supervision of machinery, the joining of broken threads, is no activity which claims the operative’s thinking powers, yet it is of a sort which prevents him from occupying his mind with other things. Friedrich Engels, The Situation of the Working Class in England (1845)

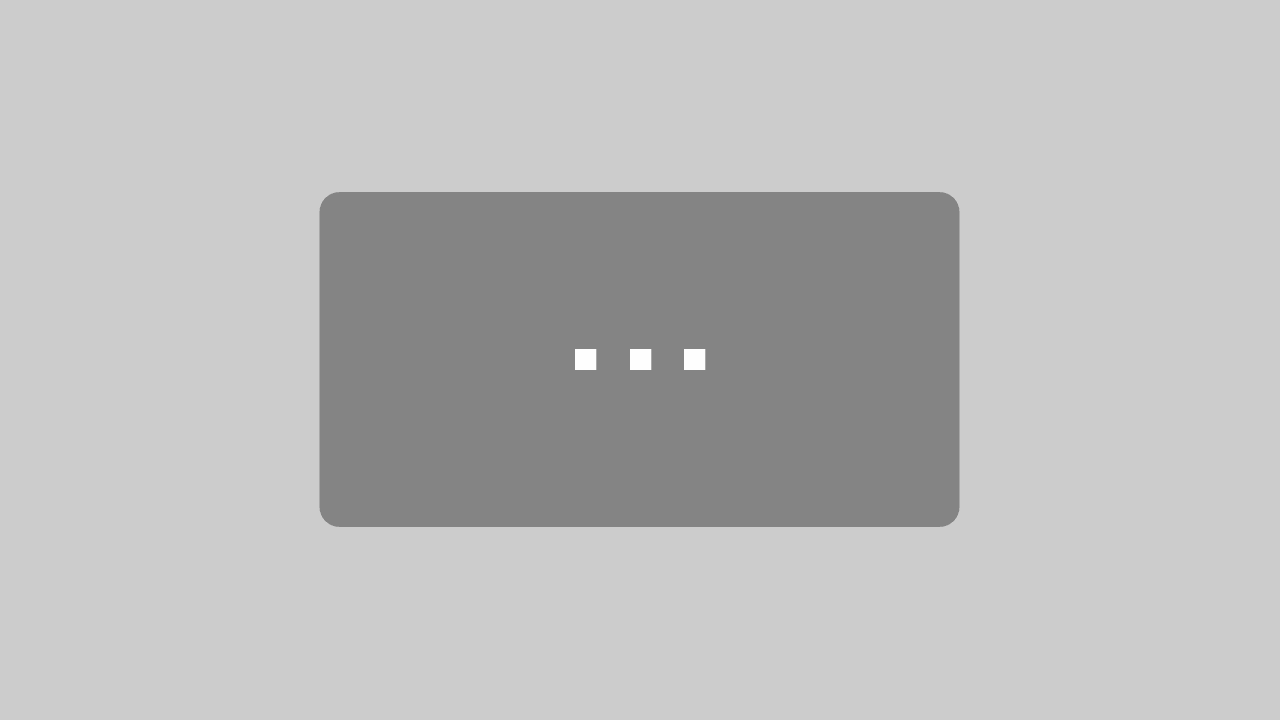

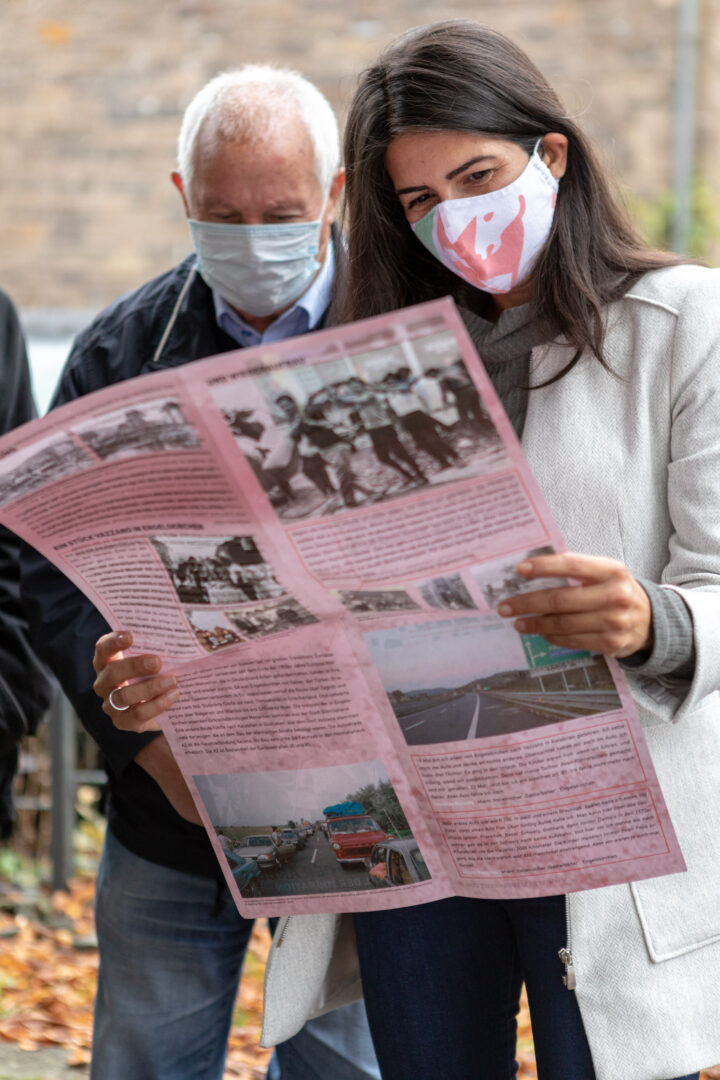

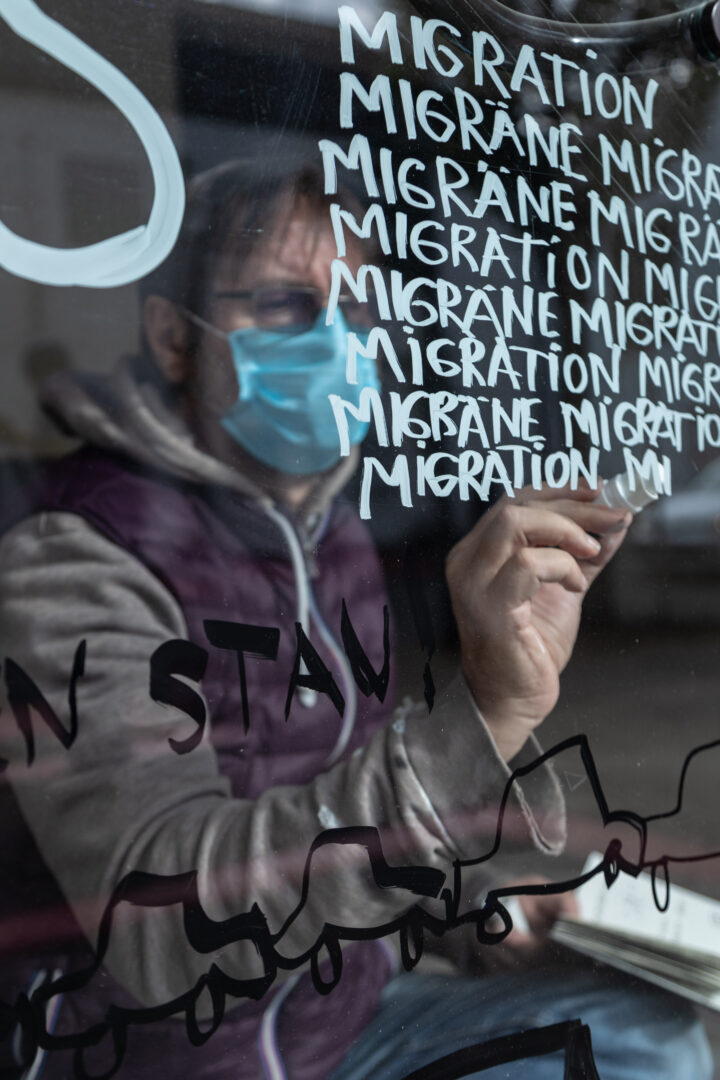

What comes after work, at least after the kind of work that prevents the “mind from being occupied with other things”? On the occasion of Friedrich Engels‘ 200th birthday ten artistic positions in Engelskirchen examined the intellectual and political legacy of the influential political thinker and activist: What does work mean today, in a time of serious crises and changes? How much is our life interwoven with work – hasn’t it even become a form of work itself? Who stands in the light, who remains invisible? How many of our occupations are activities that no one really needs, but which are often far better paid than those that are actually “system-relevant”? So what is it today anyway: the “working class” – in an era of global markets and networks, digital monopolies and new class struggles?

The history of the municipality of Engelskirchen is closely linked to that of each of the Engels family: in 1844, the Ermen & Engels cotton spinning mill began production, a factory based on the efficient English model. Apart from favourable transport routes and the Agger river, which supplied both energy and water for dyeing the yarns, there was another good reason for the choice of location: sufficient women and children as cheap labour. So while Engelskirchen was preparing to become one of the engines of the Industrial Revolution, Friedrich Engels Jr. wrote his seminal book on The Condition of the Working Class in England, which can be read in passages as a description of what was then just beginning in this region.